Under Zine El-Abidine Ben Ali’s regime, the state forcibly spoke on behalf of all citizens and imposed specific delimitations on universal concepts. After the revolution, the public space has been opened to new democratic debates, including the question of freedom of conscience. This issue caused heated discussions in the halls of the Constituent Assembly, which was entrusted with the task of writing a new constitution establishing a Second Republic. Yet, although the deliberations have ended with constitutionalizing freedom of conscience, the concept still not clearly defined.

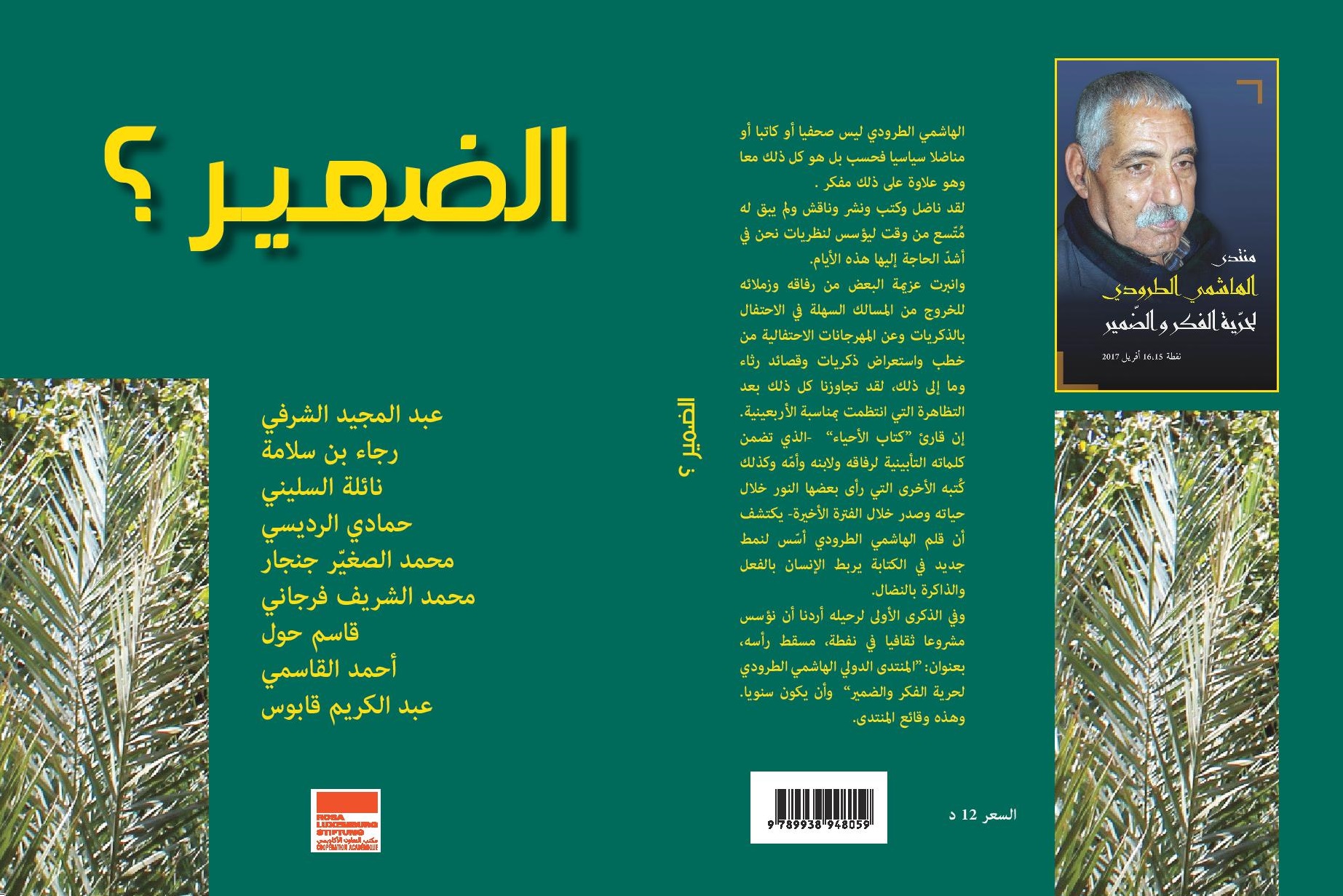

This book falls in the broader context of the debate, and includes contributions prepared by a group of prominent Tunisian intellectuals to the first edition of “The Hechmi Troudi forum for freedom of thought and conscience”. In partnership with the Academic Cooperation Office of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation, the forum was held on 15 and 16 April 2017 in the city of Nefta, which is the hometown of Troudi (1944-2015).

The forum was headed by Abdelmajid Charfi, while the book was coordinated by Abdelkarim Gabous. In addition to a working paper entitled “Freedom of Thought and Conscience: which Approach within the Framework of Arab and Islamic Transformations?” the book included nine other papers and an introduction, all of them in 159 pages.

The working paper relates the reasons behind selecting the conscience issue to the journalist and author Hechmi Troudi, since he experienced “the problematic of Freedom of Conscience” by graduating from a traditional Islamic school, and being involved later in the leftist movement, the thing that allowed him to blend “Strict Secularism and Islam” without being forced to abandon any of them.

The opening lecture by the head of The Tunisian Academy of Sciences, Letters and Arts “Beit al-Hikma”, Abdelmajid Charfi, makes it clear that the focus is directed towards empowering the Freedom of Conscience. He tries to explain the transition from traditional societies that are based on simulation and Hierarchy to modern societies, the occurrence of “Individual autonomy” and the related values and principles, especially “Freedom of Conscience”. Unlike the contribution of Gabous that is entitled “Our Sheikh Hechmi Troudi: the First Teacher”, the rest of the papers deal with general topics from different perspectives.

Based on legal interpretations andher personal experience in psychoanalysis, Raja Ben Slama tries, in her text “What is the Freedom of Conscience in Tunisia”, to clarify the meaning of the concept by shedding the light on some neglected intersections between religion, gender and cultural identity. As for Mohammed Cherif Ferjani, he emphasizes in his paper “Body and Freedom” the idea that freedom of the body must be one of the top proprieties. Besides, through her text “Women and what they consider sacred: a Call to review presuppositions”, Neila Sellini analyses the religious interpretations that still maintain the inferiority of women.

From a philosophical perspective, Hamadi Redissi also focuses on “Freedom of Conscience” which he considers “silent, unlimited and suffering”. Ahmed Guesmi’s paper revolves around “The Tunisian Artists and the Freedom of Conscience: Constitutional and Non-Constitutional Obstacles”. In his text “Shiite, Communist and the Conscience Between Them”, the Iraqi writer and filmmaker Kassem Hawal examines the evolutions of his life and his rich career. At last, the Moroccan writer Mohammed Seghir Jinjar analyses the “Double Standards and the dimensions of the Moroccan constitution’s silence on the Freedom of Conscience”.